25 nov Lessons from Harvard

From the 26th October until the 6th November 2015, together with a diverse group of 68 Young Global Leaders (YGL’s) from all over the world, I had the privilege to attend the intensive course ‘Global Leadership & Public Policy for the 21st Century’ at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Our participation was made possible by a number of generous donors who literally said: “Our generation screwed up. It’s up to you to fix it and we want to help you with that”.

Lessons from Harvard

It was heavy being away from home, my husband and three young children for two weeks. Our days were intensive and long, but it was a fantastic experience! Never before in my life was I as focused and attentive in the classroom, or listened as closely and learned so much in such a short time. The content was so unbelievably absorbing and the group so studious and challenging.

It would be too much to summarize the entire two-week course in this one blog post: classes were running from 7:00 – 18:30, followed by dinner until 22:00 and then tens of pages of homework. However, I’d really like to share the most valuable lessons to me, which, in many ways, gave substance to things I have been feeling and experiencing for years.

Immediately after returning, I started to add these lessons to my presentations and they’ve been having a big impact on people already.

Below, you will find the five lessons I’d like to share with you, which relate to the following topics:

-

- The importance of diversity

- The (in)security of one’s identity

- Being prepared for the unknown

- Personal leadership

- Biases & ‘nudging’

Lesson 1: The importance of diversity

Professor Ricardo Hausmann developed the Economic Complexity Index. He showed us that the economic prosperity of a geographical area (city, region or country) is linked to the diversity, uniqueness and complexity of economic activities within this area, and with the pace in which this diversity ensures cross-pollination; in other words: the more (different) industries exist in a certain region and the closer these industries are connected to each other, the more economically prosperous this region becomes.

Hausmann recommends that we set aside ‘specializations’ or ‘silos’ at a geographical level, as these do not contribute to economic growth. He is, however, in favor of specializations at an organizational level– such as specialized companies and teams, able to influence others with their unique knowledge and skills.

.

You can read more on the ‘Atlas of economic complexity’ here.

Ecosystem

This makes a lot of sense to me. And I can’t help but compare it with what happens in nature: a more diverse ecosystem is a stronger ecosystem. In a strong ecosystem, there is no “Higher” and “Lower”. Yes, some species are higher ranked in the food chain, but that doesn’t make them any better or more valuable.

I dare say that Haussmans’s theory and the factors of diversity, uniqueness, complexity and proximity, apply also to individuals. In other words, the more diverse a population, the more people with unique knowledge and skillsets available, and the easier access they have to each other (a.k.a. how strong their network is), the better it is for the prosperity of this population. I believe complex knowledge develops when a group of people is able to create new and ‘out of the ordinary’ connections among seemingly irrelevant themes. I would dare say that when students and learners are able to make such connections themselves, they create unique and complex new knowledge.

Imagine what happens if we (further) cultivate the above mentioned factors in education and personal (talent) development… How would our communities look like then?

Lesson 2: (in)security about one’s identity

Professor Phillip Goff (“Dr. Phil”), a guest lecturer from UCLA, who specializes in racial issues, used a very refreshing (or, for some, inappropriate, not politically correct) language. He has done groundbreaking research on the importance of identity – and the danger of being insecure about one’s (mostly masculine) identity.

Goff researched the Ferguson case (the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mississippi), where white police officers shot a black man. After he measured the agents’ testosterone levels, he let them participate in simulation cases of multiple scenarios, including scenarios in which they had their masculinity challenged (“You think I am not man huh?”).

His research shows that police officers who were insecure about their masculine identity, demonstrated escalating behavior much more often. In fact, these officers showed their preference to being assigned to black (problem) neighbourhoods; that is, in neighborhoods where they could assert their masculinity.

During the class, we had heated discussions over these findings, because we felt strongly that similar mechanisms could apply in other situations. Goff confirmed that this factor plays a role also in the recruitment of IS fighters (article on the matter soon to be published), as well as in the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. (He said he already published something on the topic, but so far I can’t find anything about it).

After the lecture, we discussed whether this ‘masculine identity issue’ may also play a role in the leadership style of many bosses, bankers and traders. You can probably guess our suspicions…

Lesson 3: Be prepared for the unknown

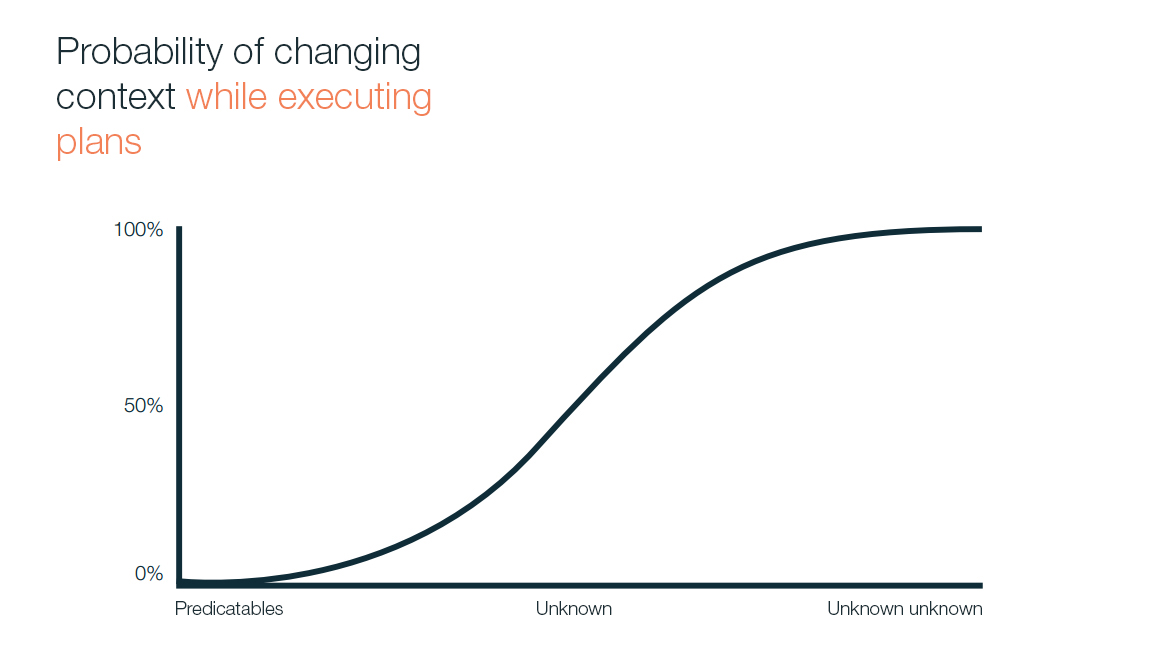

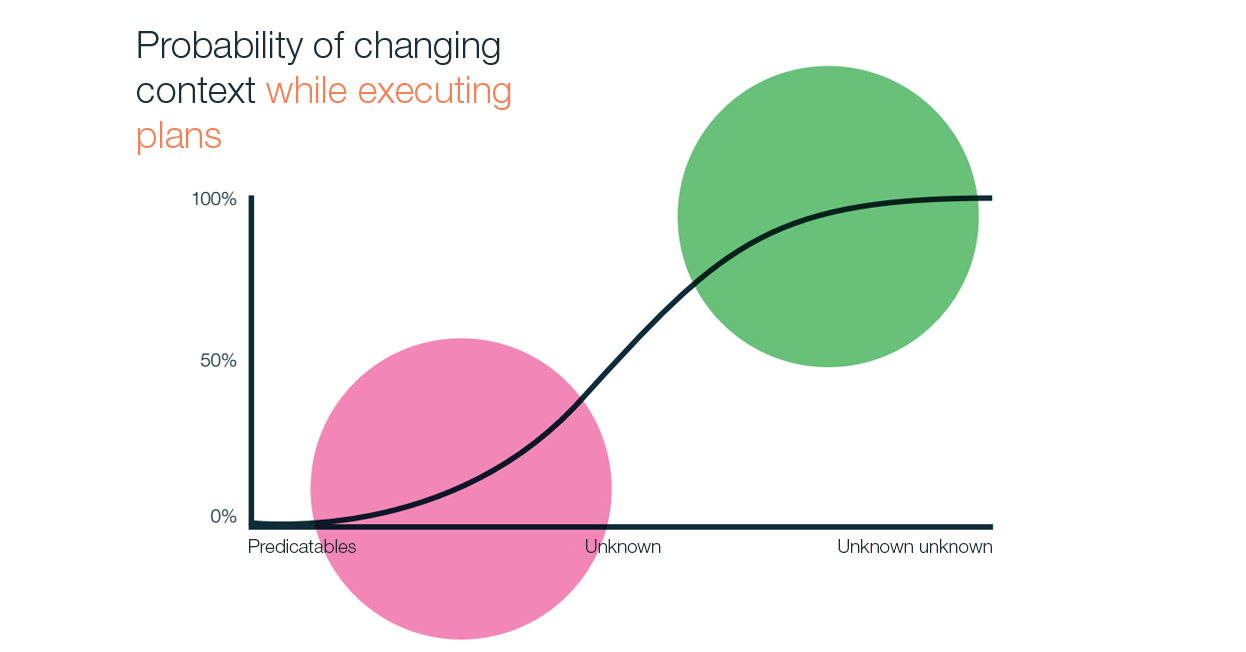

Professor Dutch Leonard (his name is actually Herman, but because of his Dutch roots, people always call him ‘Dutch’) gave the last four lectures of the program. After his lectures, we gave him a standing ovation and tears ran from my eyes. My tears were induced by a song he sang for us, which was vulnerable and pure (“You’re going to build a road, and it’s going to the sun”), but also because of the model below. It explains and reinforces so much of what I have come across in life.

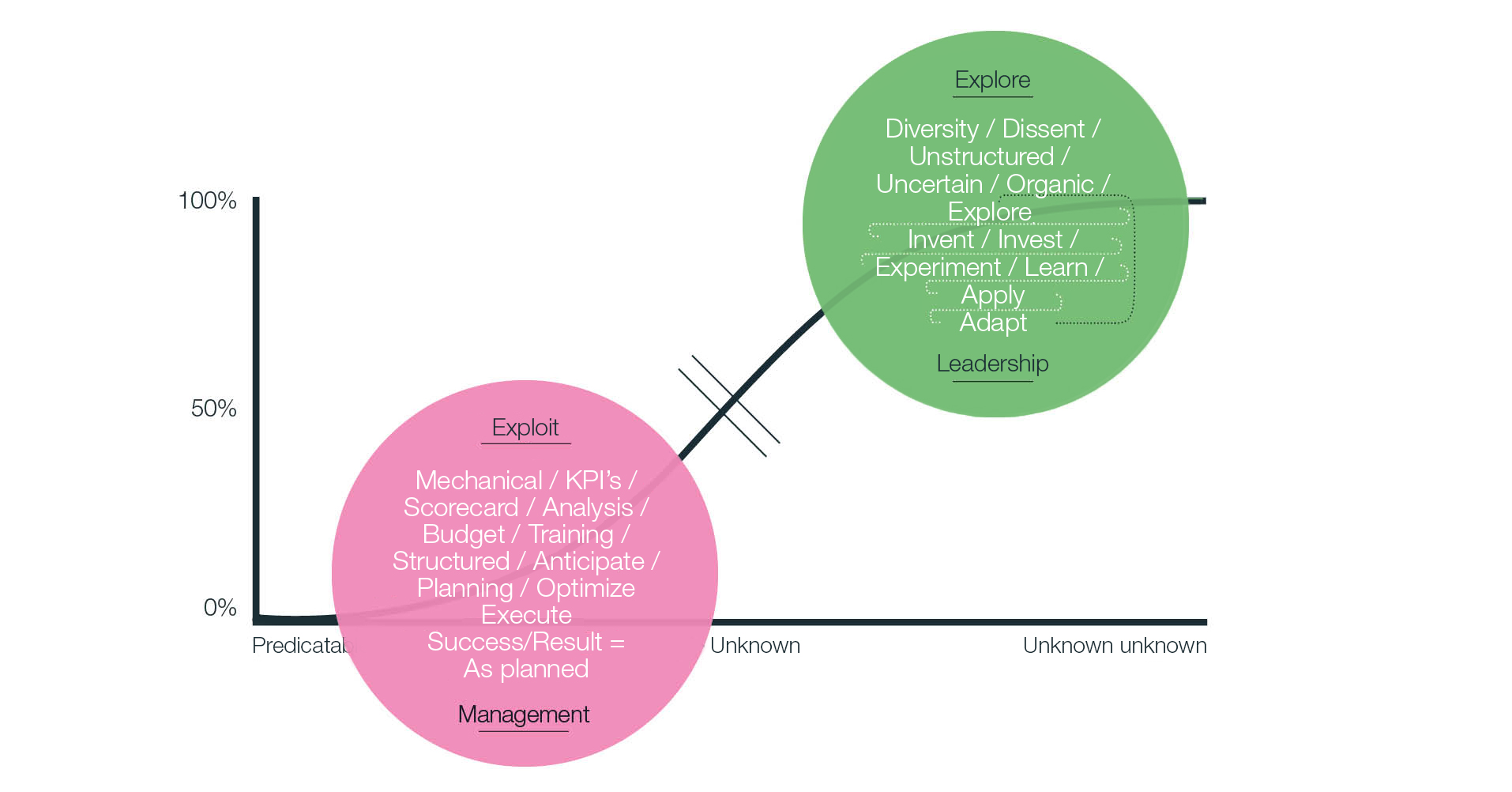

The vertical axis relates to the chance that a certain context changes while you are busy making plans. On the horizontal axis, first, you have things or situations that are predictable or certain (the “predictables”), then the ones that are uncertain (the “unknown”, for example the effect that self-driving cars will have on our society: we know they will come, but can’t really tell how exactly things will change in our lives) and finally the ones completely unpredictable (the “unknown unknown”; such as the impact robots and artificial intelligence will have on our lives in the next twenty years). If we draw a line between these points, we get an S-curve graph.

Dutch Leonard shows us that that the type of organization required to deal with situations at the bottom-left corner of the graph, is a totally different type of organization than that at the top-right of the graph:

We studied some diverse (extreme) cases, such as a fatal Everest expedition, the Endurance South pole expedition by Ernest Shackleton and the successful rescue operation of Chilean mineworkers trapped at 700m below the earth’s surface. We wanted to see what type of leadership is needed in each situation. This was the result:

Exploitation versus exploration

In situations where everything is predictable and the chance of changing plans is unlikely, it is best to bet on what Leonard calls ‘Exploit’ or management. This involves concepts such as KPI’s (“Key Performance Indicators”, or critical success factors), budgets, scorecards etc. Success and results are measured by the extent you are able to execute your plans.

In what we called an ‘Unknown’ situation, it is sometimes possible to adopt the ‘Exploit/ management’ style – in an attempt to make the unknown manageable. But at a certain moment, the levels of uncertainty and change become too large – causing this style to do more harm than good. One has to switch to the ‘Explore/ leadership’ style and organization.

In this situation, everything is new and has never been done before. In order to function well in totally unknown situations, you need a team that can respond well to the unknown. Research shows that the more diverse the backgrounds and perspectives of team members, the higher the quality of analysis of the task at hand. An important word here is “dissent”: “the expression or holding of opinions at variance with those previously, commonly, or officially held”. In other words, having and expressing different opinions.

In this case, you have to first explore (what’s happening here?), then invent, and invest in your findings, experiment (what works and what doesn’t) and based on those findings you learn and further execute. Based on the results and feedback obtained, you adjust and explore again. This is a truly organic process. And it can only be lead by very skilled, or (I dare say) masterful leadership. Which is not to be confused with ‘playing the boss!’, and is completely different from good management.

Revelation

For me, this diagram came as a big revelation. It described exactly what I have been experiencing and feeling my entire life! My work experience has mainly been within ‘Explore’ teams and environments but ended up being judged under the ‘Exploit’ lens. I remember very vividly an appraisal meeting with my manager who said: “Yes Claire, I know that last year the context changed dramatically; but we agreed on these KPI’s together, and you did not manage to reach them, so I can’t give you a score higher than “satisfactory”.

During the past few weeks, also, other YGL’s recognized this as a very familiar situation. Almost everyone experiences similar situations in which uncertainty becomes ‘managed’ with endless KPI’s, criteria and structures. Interestingly, it seems that with increasing levels of uncertainty and change in society, organizations seem to do even more of “Exploit” – building in ever more accountability systems in a desperate attempt to keep control of the situation, but with a devastating effect on all stakeholders.

And for myself, I realized that my entire life, I had confused ‘management’ with ‘leadership’ and thought I could not be a leader because I am only a moderate (or I dare to say bad) manager…

Exploration and leadership in education

How would the world look like, if we embraced exploration, so we could better empower people and teams? We can still (in a number of situations) hold on to management, but in this fast-changing world, we’d better become exceptionally good at exploration and leadership… And how do we cultivate such extraordinary leadership and from what age do we start? How can we prepare schools to become exploration organisations and get teachers to become leadership virtuosos?

Lesson 4: Personal leadership

During the course of these two weeks, we dedicated every day about one and a half hour to our own personal leadership style – mostly during our “Leadership circle” breakfast sessions. We used as a guide the method, the book & fieldbook of Professor Bill George, “True North”.

Bill George was the gifted CEO of Medtronic, the world’s leading company in medical technology. During his time as the company leader, he increased its value (market capitalization) by 35% a year, from $1 billion to $60 billion. Nowadays, he is a professor at Harvard and supports leaders of all levels in finding their own “True North” – in finding their own and unique passion and unleashing their authentic full potential while embracing their entire personality.

Crucibles

His lessons touched us deeply. He also received a standing ovation from us, after he shared some very personal experiences that made him into the person he is today. Only after going through these experiences (he called them ‘crucibles’; these very heavy, difficult and often transformative phases of our life that shape our character) and being able to accept and embrace them, he could really grow as a man and a leader.

These crucibles are our life’s pathways, what made us who we are today, our struggles. Coaching and personal development — let alone therapy — are still things that take place in the private sphere – and still seem to be a taboo topic to discuss.

He told us that from the numerous male leaders he interviewed, at least 70% (!!!) of them had a serious conflict with their father; and that this explains much of their frustration, megalomania and desire to prove themselves. According to George, they would be much better (and much happier) leaders, if they could come to terms with their crucibles and ask for help through, for instance, therapy, coaching, family counselling etc.

At the other end, successful women have often empowering mothers – but loyalty issues and the need to prove oneself also play a role.

We discussed all of this in our ‘leadership circles’- intervision teams in a setting of trust in which we dive deeper into our crucibles, journeys, and challenges.

These leadership training have made me a much happier, balanced and impactful person. And even though I still have a lot of work to do, I really enjoy this ‘trip towards the inside’ that I’ve been very consciously taking a couple of years now.

Lesson 5: Prejudices and biases

During the first few days of the course, we were bombarded with lectures about biases, led by Faculty Chair, Iris Bohnet. They were all about preconceptions (or habits), and how these unconsciously or consciously influence how we act and make decisions.

Seeing is believing

Biases play a big role mostly in the field of gender (man or woman) and race (white or coloured). If you only see very few women in leadership positions, while you mostly see white elderly men leaders in the media and your environment, you are inclined to think that this group makes the best leaders. We call this an ‘availability bias’ (seeing is believing) or ‘confirmation bias’ ( seeing things that confirm your own standpoints/ beliefs/ convictions).

The effects of these biases are everywhere. What we are exposed to in our environment, plays an enormous role in what we think (and feel) is “good”.

Nudging

The best way to influence this behaviour is by ‘nudging’ — which literally means to give gentle pushes. An example of nudging could be the exclusion of names and photos from job applications since names and photos often (unconsciously) give a ‘wrong’ impression of the candidate. Think, for instance, how a name like Mohammed, or the photo of a woman with a headscarf, could, in the western world of today, negatively affect these candidates in the application process.

We’ve all dealt with this behavior one way or another — and it is extremely difficult to separate our ‘true’ intuition from our biases because they have been fed by the media and our surroundings for years. The most effective way to deal with our biases is to become really aware of them and build ways within our systems that will allow us to bypass them. This video commercial by a big soda brand showcases exactly this, that “labels are for cans, not people”.

In education, I see these availability and confirmation biases in (i.m.o. restricted) discussion about education in the mass media as well as social media. It is up to us to take these discussions to a much deeper and fundamental level and make more visible the good examples of schools and other learning environments that address modern education.

Sharing insights

There were many more exceptional lectures; About negotiations (lesson learned: always have a “BATNA” (Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement) in the back of your head and don’t be afraid to look — even after you came to an agreement — how you can still increase the “win” for both parties); About healthcare (shocking realization: in the US there is no maximum limit on the expenditure in healthcare innovation – an important reason why healthcare costs have skyrocketed); About attitude from TED star and fellow YGL Amy Cuddy, (lesson learned: if you make yourself literally ‘big and strong’ — i.e. take a “power pose”– for an important meeting or gathering, you will have a better chance coming across as confident), as well as algorithms and data.

I truly enjoyed my two weeks at Harvard, but I really believe I should not have been there just with 67 other YGL’s. Everyone who works in learning and education should have access to the powerful insights, knowledge and experiences that we had. We are all leaders facilitating young people in a world of uncertainties and we need to help them navigate their way into the future. We, therefore, need to work on our own personal development. As a society, we owe it to our children that the right teachers are in place, that we appreciate them and provide them with the right level of support. All teachers should be able to go to Harvard!

This experience was also for me very transformational and has given me great new insights. I hope that this blog post will have a scalable impact and further feed the movement to transform education. Use it as you see fit and share it, so we can all become part of this big movement.

If you’d like to learn more about these lessons in person or to share them with a bigger group within your organization, please do get in touch! Together we will see how we can make it happen.

….

Translation from Dutch: Edith Kraaijeveld, Eleftheria Karyoti